SI SEYMOUR’S LEGACY (Part Two): Why Design for Fundraising Had a Career-changing Impact on Me

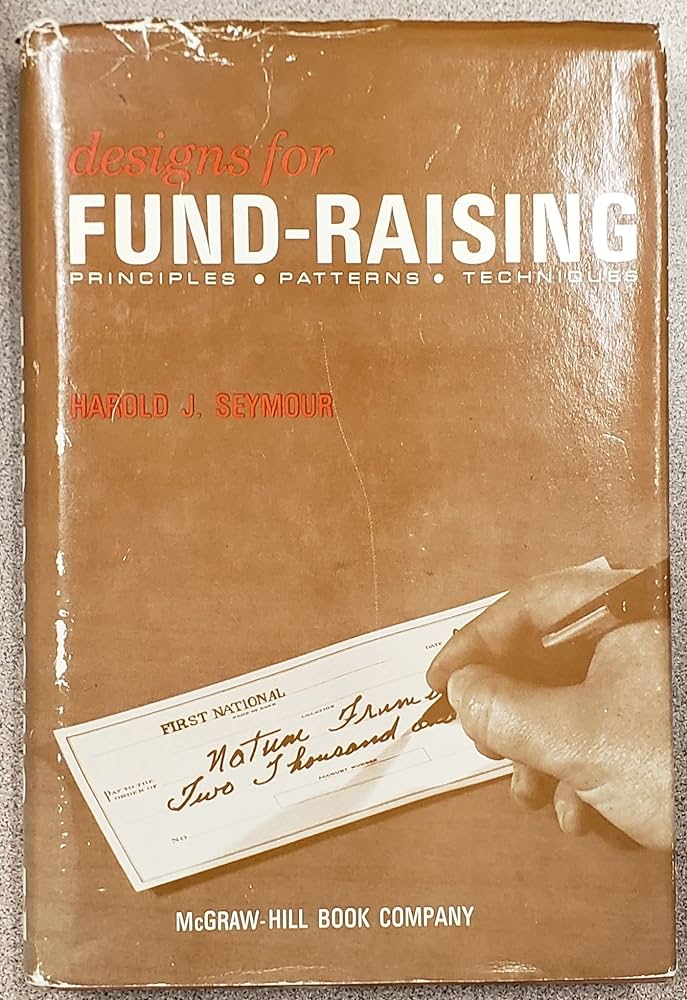

As a rookie fundraiser at a small liberal arts college, Si Seymour’s 1966 book, Design for Fundraising, had an extraordinary impact on me, so much so that it has been the primary inspiration throughout my 45-year career. Every page of Seymour’s little book resonated with me so deeply because I had been mentored in the art of donor relationships since elementary school.

As a rookie fundraiser at a small liberal arts college, Si Seymour’s 1966 book, Design for Fundraising, had an extraordinary impact on me, so much so that it has been the primary inspiration throughout my 45-year career. Every page of Seymour’s little book resonated with me so deeply because I had been mentored in the art of donor relationships since elementary school.

My dad, Robert C. Thompson (1929-2008), understood people’s motivations and emotions. By the time he was sixteen, his father had passed, and his mother had abandoned him and his two younger siblings. He took on the responsibility of raising his younger brother and sister as his dreams of going to college and becoming a dentist quickly faded away. Instead, he went to work at Bitzer’s Auto Sales and Service, washing cars and changing oil.

The same unfortunate circumstances that limited my dad’s opportunities ignited in him a fiery determination to not allow that same thing to happen to other kids. Whenever my dad became aware of a high school graduate in our community who had the aptitude and desire to attend college but could not afford it, he personally took up their cause and became their champion. As a result, he became like a patron saint of poor and middle-class kids from my hometown of Salem, Illinois, with a population of about 3,000 in 1963. His objective was to help young people who wanted to continue their education.

Not only was my dad unable to attend college, he had never attended a university function or even met a university fundraiser. Yet his intense passion for education and opportunity was infectious. We would travel around the state of Illinois talking to farmers, bankers, and business owners, asking them to give money for a kid’s tuition. Some of my earliest memories were sitting next to my dad in the front seat of our 1952 Plymouth with my arm on his shoulder as we drove around the state, paint rippling off the back fender from dad’s do-it-yourself paint job. As I can remember, he helped to raise the full tuition for 23 kids to get through college. Most of them graduated, and many became incredibly successful, including one young man who became Vice President of Pepperdine University.

And that’s how, as a young boy, I learned what it meant to be a fundraiser.

TOP TEN LESSONS CONTINUED

In my last post, I explained the top five takeaways from Seymour’s book:

SEYMOUR #1. “People want to be considered worthwhile members of a worthwhile group…”

SEYMOUR #2. “One of the most important things for persuaders to remember about people is never play down to them but always approach them with due respect for their idealism…”

SEYMOUR #3. “By all means keep the posture of willingness to tell all, but leave a little room for dreams. All other things being equal, people can always fashion in their own hearts a far better rationale for their support than any of us could ever devise from any long parade of facts and figures…”

SEYMOUR #4. “The soul of a people looks back with pride and affection (to the organizational story)…”

SEYMOUR #5. “Giving is primarily reactive. People seldom give serious sums without being directly asked to do so…”

My top ten list of things I learned from Design for Fundraising about people and their motivations to give continues below:

SEYMOUR #6: “Tax-talk facilitates giving but is seldom the prime mover. The place for this… is after the donor has decided to give.”

Since 1966, when Design for Fundraising was first published, there has been a steadily increasing percentage of donors who do not trust governments to efficiently and effectively solve healthcare, environmental, or economic problems. Rarely do I ever hear donors say they would rather invest their social capital with the IRS. They instead opt to give to charities because over 70% of donors believe the money will be used in ways that are more efficient and consistent with their core values.

Rarely do I ever hear donors say they would rather invest their social capital with the IRS.

When it comes to strategic applications of funding to solve long-term systemic problems, one essential fact stands out—the more politicized the process, the less focused the attempted solution.1

SEYMOUR #7. “Giving begets giving.”

Passionate giving is contagious. The best way to catch it is by coming in contact with people and organizations that are creating a significant impact in worthy causes. Conversely, that same passion to give subsides with isolation from real people meeting real needs.2

Dr. Paul G. Schervish, professor of sociology at Boston College, documented the self-narratives of 130 millionaires (Gospels of Wealth, Praeger 1994). The accumulation of wealth was a central theme of each story. Schervish observed that almost every one of these autobiographical accounts followed the outline of the classic hero’s journey. As in Homer’s “Odyssey,” the stories typically began with a virtuous struggle against obstacles to change the fate that was dealt to them. Somewhere along the way in their journey, most of Schervish’s millionaires began to reframe the meaning of their own story (and their wealth) in terms of philanthropy.3

SEYMOUR #8. “People love winners. This is a part of our folklore and by now should be an accepted legend of fundraising—that support flows to programs rather than to needy institutions.”

All nonprofits are by nature needy, yet some are defined by their desperation more than their vision. Si Seymour represented institutions with sizable endowments, such as Harvard and Princeton Universities, and served as a fundraiser for organizational initiatives he helped develop from start-ups (National War Fund during World War II, youth groups, and numerous community service projects). The differences between “promising” and “needy” causes are often a function of institutional leadership rather than the persuasiveness of individual fundraisers. People love winners because they have demonstrated predictability, sustainability, and margin in the long-term fund development process.

Donors are attracted to organizations with funding predictability. Numerous nonprofits perpetuate a sense of need by self-imposed crises.

Donors are attracted to organizational sustainability. Program expansions or funding initiatives that ignore competitive staff salaries and outdated infrastructure are a sure sign of short-term thinking.

Donors are attracted to the broad-based cultivation of additional donors.4

SEYMOUR #9. “All fundraisers should note that many try to do by mail what we used to do by personal visitation…”

Donors and nonprofits have undergone a cultural sea-change since Design for Fundraising was first published in 1966, particularly in terms of social and mass media communications. Today, nonprofits tend to solicit funds from a much wider audience of prospective donors—not just locally but regionally, nationally, and internationally. Additionally, the number of nonprofits has grown exponentially—rapidly outpacing the growth in population, charitable giving, and economic growth. Nonprofit communication with donors is far less expensive, far less labor intensive, and much timelier than it used to be. But, many nonprofit leaders suggest that mass media communications (email, websites, text messaging, etc.) have not improved fundraising effectiveness.

For every 1,000 broadcast emails delivered, nonprofits raised $45 (i.e. less than 5 cents per delivered email).

Nonprofits raised $0.83 per website visitor in 2018. Overall, 1% of website visitors made a donation.

Only 13% called to say thank you in response to an online donation.5

The more important question is whether the communication strategy of distant, non-personal donor relationships is effective enough to keep pace with the rapidly changing culture.

SEYMOUR #10. “Every cause needs people more than money.”

There seemed to be no end to my dad’s appreciation of character and generosity. He used to tell stories about shining shoes as a boy. As I recall, hard work was the point he was trying to get across, but he couldn’t get through stories without making frequent comments about his shoeshine clients, particularly men who had gone out of their way to help him. In his later years, he still talked about those few men and everyone else who had ever done anything for him. His sense of appreciation for any act of kindness never waned.

Fundraising software enables us to track and analyze every aspect of giving to an organization—one-time givers, repeat givers, gift frequency… and lapsed donors. This valuable data can unintentionally lead to a “What have you done for us lately?” relationship with donors who have played significant roles in the history of the organization.

As the new kid in the development department, I was presented with a large stack of lapsed donor files and got busy following dad’s example, meeting with previous donors to express our thanks for the difference they had made. A few of those follow-up appointments turned into institution-changing gifts.

My dad would have never understood the concept of “lapsed donors.”

Each one of Seymour’s points echoes the foundational examples of philanthropy embodied through my father: passion, generosity, and personal relationships.

I first read Si Seymour’s Design for Fundraising in 1979. Its central theme of caring about people more than the institutional process resonated with me and served as a reminder of every lesson imparted to me as a boy. Each one of Seymour’s points echoes the foundational examples of philanthropy embodied through my father: passion, generosity, and personal relationships. I always knew I would be a fundraiser; I never considered doing anything else. I’ve been asked who I consider to be the greatest philanthropist I’ve ever known. Without a moment’s hesitation, I say, “My dad.”

Eddie Thompson, Ed.D., FCEP

Founder and CEO

Thompson & Associates

1 R. Edward Thompson, April 26, 2021, SOCIAL CAPITAL: Investing in Federal Programs or Self-directed Philanthropy?

2 R. Edward Thompson, June 13, 2022, MANAGING GENEROSITY: When Donors Feel It’s Time for a Giving Audit

3 Edward R. Thompson, Nov 17, 2014, PARADIGM SHIFTS: Inspiring Philanthropic Awakenings Among the Already-Generous

4 R. Edward Thompson, June 2013, INSTITUTIONAL SUSTAINABILITY: Transitioning from “Hunter Gatherer” to a Cultivation-Based Fund Development Strategy

5 R. Edward Thompson, July 2020, OVER-RELIANCE ON ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATIONS: What It Can and Cannot Accomplish

Eddie,

I have enjoyed these last two articles very much! I wish I could find a copy of that book. I have been looking to no avail. Also, I have heard you tell those stories about your dad before and it’s inspiring each time I hear it.

Dave, yes! I tried to track down a seller of Si’s book, as well. I hate that it’s not in print anymore.