LEADERSHIP CONTINUITY: Retaining Top Talent Amid the Great Resignation

There have been some monumental changes over the last two years, among the most significant is the labor shortage at all organizations (for-profit and nonprofit). It was first described by Anthony Klotz, Associate Professor of Management at Texas A&M University, as “The Great Resignation.” In April of 2021, more people quit their jobs than during any month in almost a century (Nonprofit HR). What is more surprising is the trend among those who are now returning to the workforce. According to a Grant Thornton survey, of the 21% of American workers who found new jobs in the past 12 months, 40% are already looking for other employment. Tim Glowa of Grant Thornton commented on the active job seekers. “They (employees) made the recent switch, and it proved to be very easy. So, they’re willing to make that switch again.”

There have been some monumental changes over the last two years, among the most significant is the labor shortage at all organizations (for-profit and nonprofit). It was first described by Anthony Klotz, Associate Professor of Management at Texas A&M University, as “The Great Resignation.” In April of 2021, more people quit their jobs than during any month in almost a century (Nonprofit HR). What is more surprising is the trend among those who are now returning to the workforce. According to a Grant Thornton survey, of the 21% of American workers who found new jobs in the past 12 months, 40% are already looking for other employment. Tim Glowa of Grant Thornton commented on the active job seekers. “They (employees) made the recent switch, and it proved to be very easy. So, they’re willing to make that switch again.”

IMPACT OF THE GREAT RESIGNATION

Even before the pandemic, “the voluntary annual turnover rate among nonprofits was 19%—63% higher than the all-industry average of 12%.”1 In June 2019, a survey commissioned by The Chronicle of Philanthropy and Association of Fundraising Professionals was sent to Chronicle subscribers and AFP members. Among the 1,035 responders, 90% were either frontline fundraisers or executive leadership. Forty-six percent worked for organizations with revenues ranging from $1 million to $10 million. The results published in 2020 were as followed:

—51% planned to leave their current nonprofit within 2 years

—30% planned to leave fundraising altogether

—12% planned to retire or have family changes or personal reasons for leaving the profession

Of course, planning to leave and actually resigning are two different things. So, what effect is the employee churn of “The Great Resignation” having on nonprofits? That’s hard to say for several reasons: First of all, data is often collected as survey responses among a relatively small number of respondents. Secondly, those choosing to participate in a survey are usually self-selected, perhaps with an “ax to grind.” Thirdly, it’s easy to create a desired skew by the way questions are framed. In other words, the survey question: “What are the primary problems facing your nonprofit?” is likely to produce a different response than the question: “How is your nonprofit addressing the needs of your community?”

…the voluntary annual turnover rate among nonprofits was 19%—63% higher than the all-industry average of 12%.

Even with these potential biases, there is still good reason to believe the nonprofit labor trends are indeed consistent with those alarming survey results because when it comes to bean counters, nobody counts beans better than the U.S. Bureau of Labor. It’s not a political entity, just an army of meticulous statisticians who are very exacting about their data. This is what the U.S. Bureau of Labor reports about the present status and coming decade of nonprofit employment.

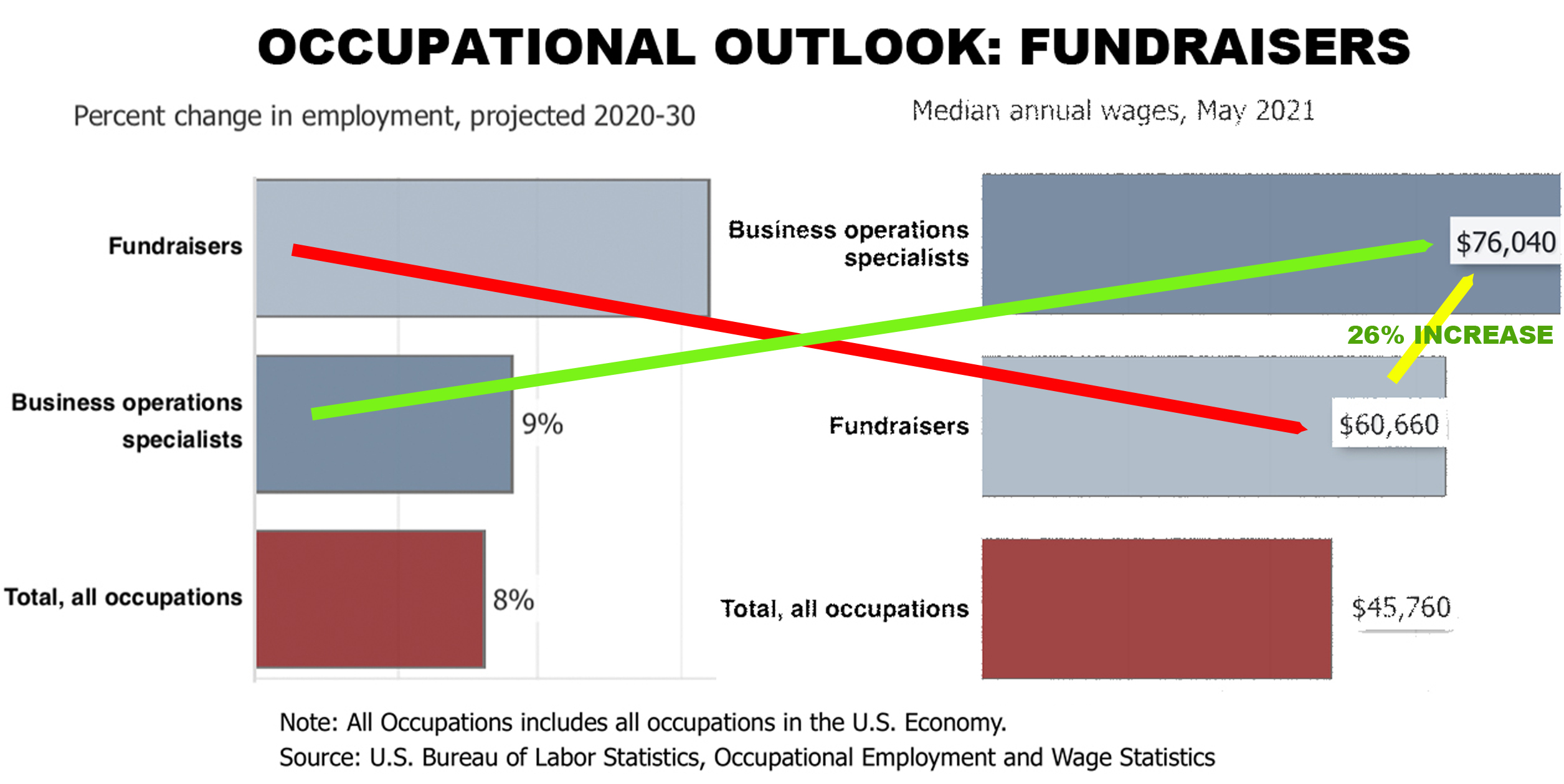

“Employment of fundraisers is projected to grow 16 percent from 2020 to 2030, much faster than the average for all occupations. About 12,000 openings for fundraisers are projected each year, on average, over the decade. Many of those openings are expected to result from the need to replace workers who transfer to different occupations or exit the labor force.” The tables below from the U.S. Bureau of Labor data:

The turnover rate among fundraisers is twice as high as the turnover rate among all occupations. Driving that turnover rate (among other things) is a 26% average salary increase to $76,040. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook, Fundraisers (visited April 18, 2022).

EIGHT REASONS NONPROFITS LOSE THEIR TOP TALENT

I presented a webinar on the topic, “Retaining Top Talent” for Crescendo’s Practical Planned Giving Conference which followed the outline of The Chronicle of Philanthropy / AFP survey that identified eight reasons why the turnover rate among fundraisers and executive leadership at nonprofits (according to the Bureau of Labor data) is twice that of other industries. Below is a summary of those results, along with some tips of my own to overcome those challenges.

REASON #1—PRESSURE: 84% said they feel tremendous pressure as organization fundraisers. Unsolicited comments included the following:

—“We can’t seem to land the BIG gift.”

—“It seems like we are all going after the same rich donor!”

—“The pressure is exhausting, and I am tired of it!”

MY SUGGESTION: To survive and thrive in the nonprofit world, organizations must transition from a “hunter-gatherer” funding strategy to one that systematically cultivates donors—becoming farmers who plant seeds, cultivate the ground, and create long-term sustainability. A hunter-gatherer approach is never short on stress. If someone doesn’t go out, “hunt down a donation,” and bring it home, the group does not survive. That constitutes the unrelenting pressure of fundraising and one of the reasons that fundraisers have such a high turnover rate.

Driving that turnover rate (among other things) is a 26% average salary increase to $76,040.

Nonprofits that start out as hunter-gatherers don’t become cultivators overnight. Skills, knowledge, and systems associated with cultivation take time to evolve. Because learning how to cultivate as a sustainable resource strategy is so labor-intensive, hunters don’t become farmers until they are forced into it.

Leaders of successful nonprofits understand that major-donor fundraising is all about sowing and reaping. If they want to expand the organizational program, they first look at expanding their development program—planting more seeds and cultivating more relationships. Short-sighted leaders, on the other hand, have a hard time resisting the temptation to expand their organizations, and as a result, they perpetuate such pressing needs that they never have the flexibility to develop a cultivation-based fund development system.

REASON #2—LACK OF APPRECIATION. 55% said they don’t believe their work is appreciated while 30% were dissatisfied with the level of recognition for their success. One responder commented, “No matter how much you do, it’s never enough!”

MY SUGGESTION: First of all, the continual need for funding is an unavoidable aspect of nonprofits. However, the irony is that organizational executives rush to shower donors with gifts and gracious words of praise, while the fundraisers are seen as only doing what they were hired to do. And if a fundraiser or the entire development team is not meeting their goals, any success is rewarded with faint praise. When the chief executive is disappointed or under pressure to perform, he/she must be careful not to take it out on his staff. I like after-action evaluations by each staff member. I prefer to highlight things I have “caught” employees doing well, followed by honest evaluations of what we all could have done better. If I have to make negative remarks about an individual’s performance, that is always a private conversation.

REASON #3—NOT ENOUGH HELP FROM THE STAFF OR THE BOARD. Though reported as a single item, help from staff and/or the Board of Directors are two different things, requiring two separate solutions. One is the CEO’s problem, the other a problem (and perhaps the more difficult one) for the Board.

MY SUGGESTION: The best-led organizations with which I’ve worked have an active Board Management Committee. This is a standing committee from the Board of Directors with the sole responsibility of educating candidates on Board member requirements and expectations. All potential new Board members are required to sign a participation pledge. The Board Management Committee also regularly evaluates members on attendance at scheduled meetings, committee assignments, and team participation. Board Management Committees are frequently established at colleges to monitor Board performance but are pretty rare at other nonprofits. Corralling and managing the active involvement of high-profile executives can be challenging, especially if those individuals are buddies with the CEO or current Board Chairman. For that reason, Board Management Committees are commonly chaired by a previous Board Chairman.

The CEO or the V.P. of Development is responsible for coordinating the efforts of organizational fundraisers. Unfortunately, development professionals at many nonprofits spend the lion’s share of their time on administrative duties rather than communicating with donors. I would rather hire one great fundraiser with two dedicated support staff than three fundraisers who spend the majority of their time stuffing envelopes. A whopping 79% of the 1,035 development officers wished they had more time to spend with donors. That was among the most frequent comments from survey respondents.

Board Management Committees are frequently established at colleges to monitor Board performance but are pretty rare at other nonprofits.

REASON #4—UNREALISTIC GOALS. Among the most frequent stress points I hear practically every day are fundraising goals that have been passed down from senior institutional executives who are not directly involved in donor relations, new donor acquisitions, or other aspects of the overall fund-development process. Pressure from outside the development department that gets passed down to the fundraisers is often a function of organizational need rather than an accurate assessment of the capacity and willingness of the donor base to give.

A subtle but very real aspect of fundraising is that whenever fund development is driven primarily by organizational need, it inadvertently becomes less and less donor-centered—but, rather, more and more organization-centered. Over time, development professionals can become so focused on mandated goals that they are only minimally concerned about whether or not the amount or the structure of a gift is in the best interest of their donors. The more hardened fundraisers consider that to be the responsibility and the problem for donors, not fundraisers.

Very rarely do development professionals start out that way but after a few years of high pressure, need-driven fundraising mandates, their approach is far more transactional and far less donor-centered. It becomes most noticeable when fundraisers are under pressure to meet funding goals, and in turn, pressure donors to give big, to give cash, and to give now. This is precisely the kind of thing that makes fundraisers hate what they’re doing and to who they’re doing it to.

MY SUGGESTION: Develop a strategic plan for organizational fund development. Of the hundreds of nonprofits with which I have worked over the years, I’ve never found one that did not have a long-term strategic plan for the institution. At the same time, only on very rare occasions have I found an institution whose long-term fund-development strategy is governed by a similar plan. Consequently, most development departments are more reactive rather than proactive. From a “Policy Governance” perspective, below are five board decisions that set the parameters of executive leadership and keep the organization on the leading edge of the “momentum curve.”

—The organization will focus primarily on funding strategies that will contribute to long-term success.

—The organization will focus on cultivating donor relationships.

—The organization will maintain a balanced approach to the solicitation of current and future gifts.

—The organization will invest in adequate staffing to effectively manage donor relationships.

—The development department will promote a culture of accountability at all levels of the organization.

REASON #5—POOR MANAGERS. The author of the Chronicle / AFP survey stated that 70% of employee departures are due to bad relationships with managers. Gallup research shows that people leave bosses, not companies. 2

MY SUGGESTION: There is no single characteristic of a good manager. So, let me give you my best personal example. I worked for a gentleman who was a really great leader. Whenever something went wrong, he was quick to say, “I’m the president; it’s my responsibility.” I’ll never forget one occasion, in front of the Board of Directors, he took the blame for something that was totally my fault. I was young, new on the job, and the one truly responsible for a lot of his problems. Privately, he’d take me aside and in a very kind, fatherly way, point out in excruciating detail what I had done both right and wrong. He was tough, kind, and willing to take responsibility. Consequently, I was never afraid of him—had no real reason to be.

Over time, he created a culture of accountability that was very empowering. People were quick to accept personal accountability (rather than hide or shift blame) and quick to credit the contributions of their peers. Whenever one of us made a mistake or fell short in any way of his expectations, we would go straight to him without hesitation, never wanting him to hear from someone else or find out some other way.

The way he dealt with me and my mess-ups helped me get over my habit of beating myself up over mistakes or missed opportunities. I would have walked on coals of fire for that man and wanted to become a leader just like him.

It’s not easy to get over a heavy dose of toxic accountability. In contrast, this executive created an organizational culture that was both empowering and highly productive.

REASON #7—Poor Compensation. Compensation at nonprofits is notoriously lower than corresponding for-profit enterprises. It’s much like the National Football League salary cap. There are certain players who have made and who will continue to make major contributions to the team’s success. Those same players also realize that their successes create a demand for their services among other teams. The hard salary cap means that teams have to make some very difficult decisions every year.

MY SUGGESTION: The key variable for both nonprofits and for-profits is WHO you have on the bus. If a person is not compulsively driven to be and do their very best, there is no amount of financial incentive that will motivate the otherwise unmotivated or undisciplined. It’s either part of their DNA or it’s not. Jim Collins writes: “The right people can attract money (donations) to your organization, but money by itself can never attract the right people.” Consequently, when you find one of those people who have both the will and the skill in the sustained pursuit of excellence, PAY WHATEVER IT TAKES TO KEEP THEM! One of the irreplaceable characteristics of great organizations is getting and keeping the right people on the bus—even if it takes years to do it. I have never had a great employee who cost me money!

The way (the President) dealt with me and my mess-ups helped me get over my habit of beating myself up over mistakes or missed opportunities. I would have walked on coals of fire for that man and wanted to become a leader just like him.

REASON #8—POOR CAREER ADVANCEMENT. When development directors resign, it’s often because they see the shortfall coming before the chief executive and board do. It reminded me of a college football coach who after many years becomes lax in recruiting the best talent. The program deteriorates, and the newly hired coach arrives only to discover the cupboard was bare of quality players. The old coach lost his commitment to long-term program success and just rode the program as far as it would take him. It happens all the time with coaches, and it can also happen with fundraising executives.

MY SUGGESTION: People who work at nonprofits are notoriously underpaid in comparison to the business world. Hopefully, nonprofit pay and benefits will increase, but given the escalating salaries all across the board, it’s going to be difficult to keep pace with the for-profit world. In that economic scenario, the key is recruiting and training the next generation of fundraisers. Among those responding to the Chronicle / AFP survey, 61% said they were dissatisfied with access to leadership training.

Since departures from nonprofits will probably continue at a rate higher than the all-industry average, executives need to recognize, recruit, and develop individuals who have the potential of being great fundraisers. Great organizations, like great sports teams, operate with a next-up mentality.

Eddie Thompson, Ed.D., FCEP

Founder and CEO

Thompson & Associates

“If we merely aim for the industry standard, then our goal is mediocrity. Emulating the average nonprofit, we are destined to live with all the problems the average nonprofit faces. So, we suggest you aim to be exceptional in your approach to fund development.”

—Eddie Thompson

copyright 2022, R. Edward Thompson