STRATEGIC MOMENTUM: John Harvard and a Series of Unfortunate Events

I wrote a paper in graduate school on the Harvard legacy and have been intrigued with the idea of it ever since. It’s a great example of several key elements of strategic giving—leverage, timing, and momentum. In other words, the greatest philanthropic impact is the result of leveraging your life situation with the right gift at the right time to the right organization, creating long-term sustainable momentum. Think of it as a man using a lever and fulcrum to start a gigantic bolder rolling down a long hill. That’s a good way to frame your thinking about the gift to the institution that became Harvard University. There are, however, sad and ironic twists to the Harvard story.

I wrote a paper in graduate school on the Harvard legacy and have been intrigued with the idea of it ever since. It’s a great example of several key elements of strategic giving—leverage, timing, and momentum. In other words, the greatest philanthropic impact is the result of leveraging your life situation with the right gift at the right time to the right organization, creating long-term sustainable momentum. Think of it as a man using a lever and fulcrum to start a gigantic bolder rolling down a long hill. That’s a good way to frame your thinking about the gift to the institution that became Harvard University. There are, however, sad and ironic twists to the Harvard story.

THE HARVARDS OF STRATFORD, LONDON

No matter how you approach the story of the Robert Harvard family, you cannot avoid the overarching theme of tragedy. In a twelve-year period, two generations of Harvards (and any prospects of a third) were wiped out. However, in the final chapter of young John Harvard’s life there was an endnote that turned out to be quite extraordinary.

Testamentary gifts are by their very nature accompanied with sadness. It is, perhaps, for that reason many avoid thinking about wills, trusts, and or even final letters to loved ones. [see A FINAL THOUGHT: What Those Last Letters to Loved Ones Can Mean] Wealth transfer cannot eliminate the pain of death but often contributes significantly to an element of legacy. In John Harvard’s case, a series of extremely unfortunate events culminated in an unparalleled legacy.

In a twelve-year period, two generations of Harvards (and any prospects of a third) were wiped out.

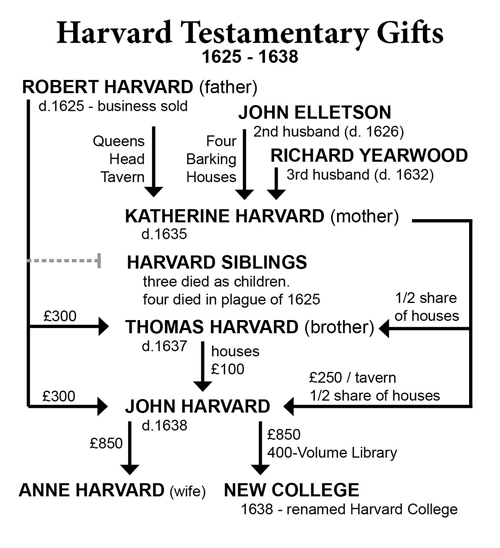

Robert and Katherine Harvard lived in (what was then) a seedy section of London known as Strattford-upon-Avon. Three of their children had died early. Then in 1625, when their son John was only eighteen, the plague once again ravaged London. Within five weeks John lost his father, four siblings and the only remaining child from his father’s previous marriage. Robert Harvard, a butcher, left £600 to be divided between John and the only other surviving child, John’s younger brother Thomas. Their mother, Katherine, inherited the Queen’s Head Tavern.

Katherine remarried within five months to John Ellerton, “a citizen and cooper of London” but was again widowed before the year was out. Though Ellerton was said to be “a man of some little property” what he did have was left to Katherine including four houses in Barking. She married a third time in 1627 to a grocer, Richard Yearwood. That third husband died five years later.

Two years after the plague, John enabled by his inheritance, began his preparation for the ministry at Emmanuel, a College of Cambridge University. The seventeenth century was a troubling religious time in England. Oxford University retained an allegiance to high-church principles, while Cambridge University and especially Emmanuel College, advocated Puritan reform. Nearly one-fourth of the university men who came to New England before 1646 had studied at Emmanuel. After four years at Cambridge, John received a bachelor’s degree and after another three, a master of arts in 1635.

John Harvard’s decision to pursue religious toleration in America upon his graduation was made easier by the fact that his mother died that same year. Katherine bequeathed to him the Queen’s Head Tavern, £250, and a half-share (with his brother Thomas) of the houses in Barking that were left to her by her second husband.

In preparation for his migration to America, John sold his share of the Barking houses as well as four other houses, while retaining Queen’s Head. Since books were scarce in the new world, John spent £200 expanding his library. At that time, £200 was almost twice the total value of the four houses he sold.

John and his new bride, Anne, set sail for the new world in 1637. Soon after the couple landed in America, John received word that his brother, Thomas, had died, leaving John another £100. The cumulative Harvard estate (estimated at approximately £2,000) had funneled down to John, the only survivor.

After the plague, nine years of preparation at Cambridge, and the loss of his entire family, John was about to begin a career which would hopefully make his mark in the new world. However, within a year he contracted pulmonary tuberculosis and died in 1638 at age thirty-one.

In 1635 the magistrates of Salem, Massachusetts had acquired 300 acres of land for a school and resolved to fund it with £400 over the next two years, an amount equal to one-third of the town’s revenue for 1636.

John Harvard left half his estate to provide for his young wife. The other half (£850), along with his 400-volume library, was to go to the new college. In 1639 the General Court at Salem resolved “that the college agreed upon formally to be built at Cambridge shall be called Harvard College.”

THE LIFE OF JOHN HARVARD by all other means would be remembered by no more than an obscure entry in the vital records of early New England. However, his testamentary gift of 400 books eventually became the largest academic library in the world. The £850 eventually turned into the largest endowment of any institution in the world. He came to America to teach and preach and wound up educating generations of New England clergy and eventually seven U.S. presidents through the new college. He had no children to carry on his name, but the name Harvard is without parallel in the academic world. At the dedication of the John Harvard statue in 1884, Harvard President Charles William Eliot called the 1638 gift a “disinterested deed of hope and faith” that crowned “a brief and broken life with deathless fame.” 1

The Harvard gift was by no means the largest ever given to the college. But, it was the most strategically significant. In other words, John Harvard leveraged his life situation with the right gift at the right time to the right institution, creating sustainable momentum.

Eddie Thompson and Walt Walker

Trackbacks/Pingbacks