FIVE IMPORTANT LESSONS; From the Greatest Fundraiser I’ve Ever Known

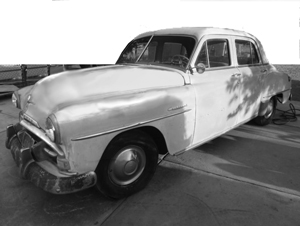

“We drove around the state (raising money) in our old 1952 Plymouth, paint rippling off the back fender from Dad’s do-it-yourself paint job.”

I have spent my whole career working as a fundraiser. I never really thought about doing anything else, and my dad is the one responsible for that. In fact, every lesson about giving that really matters, I learned from him.

It’s kind of a bittersweet story. By the time my dad was sixteen, his father was dead and his mother had abandoned him and his two younger siblings. So, Dad took on the responsibility of raising his younger brother and sister as his dreams of going to college and becoming a dentist quickly faded away. Instead, he went to work at Bitzers Auto Sales and Service washing cars and changing oil. Dad finished high school but never had the chance to go to college. The same unfortunate circumstances that limited my dad’s opportunities ignited a fiery determination in him. Dad was determined to not allow that same thing to happen to any high school graduate he knew as long as he had the ability to do anything about. That’s how, as a young boy, I learned what it meant to be a fundraiser.

Robert “Bob” C. Thompson (1929-2008)

Whenever there was a high school graduate in our community who wanted to go to college and could not afford it, my dad personally took up their cause and became their champion. He was by no means a professional fundraiser and never got a dime for his efforts. Nonetheless, my dad would travel around the state of Illinois talking to farmers, bankers, and business owners, asking them to give money for a kid’s tuition. His vision and approach were pretty simple. Kids wanted to go to college, they had no money, and we were going to help. I say “we” because even as a boy, I was somehow enrolled in his mission as something “we” needed to do. Some of my earliest memories were standing next to my dad on the front seat with my arm on his shoulder as we drove around the state in our old 1952 Plymouth, paint rippling off the back fender from Dad’s do-it-yourself paint job.

As near as I can remember, my dad helped to raise the full tuition, enabling twenty-three kids to get through college. Most of them graduated, and many became incredibly successful, including one young man who became Vice President of Pepperdine University.

I was asked recently who I considered to be the greatest philanthropist I had ever known. Without a moment’s hesitation, I said, “It was my dad.” So, here are a few simple lessons I learned from the great fundraiser and philanthropist.

LESSON ONE: It is more blessed to give than to receive.

My dad’s “random acts of kindness” were not limited to raising tuition but were at the core of his lifestyle. I remember him going out Saturdays with a can of gasoline and one of the first power lawn mowers; one that you had to manually wind the cord onto the flywheel every time you attempted to start it. When he eventually got the thing started, he would go around cutting people’s grass in the neighborhood. To my dad, helping other people was not an obligation; it was his blessing.

Some fundraisers, even after many years, are still trying to make the connection between the noble cause and the noble occupation.

As a fundraiser you have to really, really believe that it is more blessed to give than to receive. It’s not just a campaign slogan, an ethical ideal, or a Jesus saying (Acts 20:35). It was my dad’s ongoing conviction, experience, and lifestyle. That seemed to be the reason why he was such a happy person. It was also the source of his humble boldness. He had no hesitation whatsoever talking to a struggling dirt farmer or to a wealthy bank president about giving. His boldness was fueled by a conviction. My dad’s philosophy: Giving should be their decision, and if you don’t ask, you are making the decision for them. He had always been more blessed by his giving than his receiving and had no doubt that they would be too.

LESSON TWO: My dad was proud to be a fundraiser.

“Proud” is probably not the best way to describe my dad because he was one of the most unpretentious people I have ever known. Better said—he considered helping kids go to college to be a very noble endeavor.

Fundraisers are always making a case for giving. However, the first and most important case we have to make is the one we make to ourselves about our career choice. Deep down in your soul, are you proud of who you are and what you do? Some fundraisers, even after many years, are still trying to make the connection between the noble cause and the noble occupation. If you’re not proud of what you do, if you don’t sincerely believe that it’s more blessed to give than to receive, then you’ll never really enjoy what you do, and your fundraising career will never kick into high gear.

LESSON THREE: Don’t ever allow yourself to become emotionally detached from whom or what you serve.

I have a vivid memory of one particular fundraising trip. We put chains on the tires and drove the old Plymouth out a country road through some pretty deep snow. It was another adventure with Dad; pretty exciting stuff for an eight-year old. Standing in the snow, I remember that farmer in his tall rubber boots and Dad saying to him, “We really need to help these kids.” He said it with a conviction that even a young boy could understand.

I’d never met a professional fundraiser. As far as I knew, this is the way it was always done.

There is a pitfall for career ministers, social workers, and fundraisers. When doing good becomes your job, it is easy to become detached from your original intent—why it is that you do what you do. There is a difference between raising money for the hospital foundation and raising money for sick kids in that hospital. I understand that the former is connected to the latter, but I also understand how over time the process can become mechanical, and you can easily lose a personal attachment to your cause.

As a self-recruited, cause-motivated volunteer, representing no particular organization, it wasn’t hard for Dad to stay focused on those he was trying to help. At that time in my life, I’d never met a professional fundraiser. As far as I knew, this is the way it was always done.

LESSON FOUR: Failure is not an option.

Whenever my dad got involved with something, he went at it full-throttled. His persistence was remarkable. The cost of tuition was only a fraction of what it is today but so is the value of money. With each of those students needing money for college, my dad and others raised the full tuition. There was no quitting until that objective was completely done, and done well.

One day Dad dropped me off at Mabel Winterbottom’s house with detailed instructions on how I needed to mow her grass. I would much rather have been at the community pool with my friends. My lack of commitment for that particular project revealed itself in the quality of my work.

I was and am still amazed at how my dad could frame almost any activity in the context of giving.

My disappointed dad reminded me that Ms. Winterbottom was well into her late eighties and could not mow her grass anymore. He explained in great detail how she had always taken great pride in having a nicely groomed yard; how she had spent most of her life taking great care to keep it in shape. It would have been so much easier if he had just given me a paddling. Instead, I got the “talking to.”

I was and am still amazed at how my dad could frame almost any activity in the context of giving. He said, “We’re not mowing her grass, we are giving her a gift!” There was that “we” word again. I had been enrolled in another mission as my dad’s philanthropic assistant. So, the assistant got up and finished “our” gift to Ms. Winterbottom. My dad wanted me to understand that my initial lack of persistence resulted in a half-hearted gift to someone for whom he really cared.

LESSON FIVE: There was no end to my dad’s appreciation.

He used to tell stories about shining shoes as a boy. As I recall, hard work was the point he was trying to get across, but he couldn’t get through the stories without making frequent comments about his shoeshine clients, particularly men who had gone out of their way to help him. In his later years, Dad still talked about those few men and everyone else who had ever done anything for him. His sense of appreciation never waned for any act of kindness or generosity.

My dad would have never understood the concept of “lapsed donors.”

I’ve had lots of candid conversations with donors, and many have wondered out loud how long all the love and appreciation would continue if they cut back or redirected their giving to another organization. Fundraising software enables us to track and analyze every aspect of giving to an organization—one-time givers, repeat givers, gift frequency… and lapsed donors. That’s all valuable data for a sophisticated development office. However, it can unintentionally lead to a “What have you done for us lately?” relationship with donors who played significant roles in the history of the organization. My dad would have never understood the concept of “lapsed donors.”

THINGS I’VE LEARNED

As one my associates likes to say, “The most valuable thing you have to pass onto your children and grandchildren is the transferrable witness of your own life.” I learned a lot more than these five lessons from my dad; but, these five—giving as a blessing, pride in helping others, determined persistence, never-ending appreciation, and remembering who you serve—were so imprinted upon me, that becoming a fundraiser seemed inevitable. Even though the Thompson & Associates team and I have been able to direct over $6 billion to charity, I still think of my dad as the greatest fundraiser I’ve ever known.

Eddie Thompson, Ed.D

Values based throughout.

Tremendous energy from a giving heart. Well told, Eddie.

Thanks!!!

we are working to prepare and send missionaries to the Lord’s work in northeastern Brazil.

Thank you for motivating me to continue firm raised funds.

Bless.

Thanks Eddie! Outstanding words and witness.

Randy

Great article and blog. Thanks for sharing.

I wish I had had the opportunity of meeting your Dad. Clearly, he was an exceptional man, who fervently followed God’s commandments, and an exemplary humanitarian. I am confident, however, that to know you, is to know your father. You reflect every one of those, his, attributes. I have learned much from you, Eddie Thompson.