CHIEF EXECUTIVE TURNOVER: Intangible Rewards of Selecting the Right Candidate

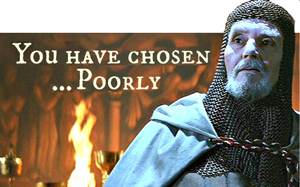

“You have chosen…poorly,” said the knight guarding the Holy Grail. The famous line from the movie “Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark,” was spoken as an intruder tried to select the of cup of Christ from over a dozen options. If he chose well, he would live forever. However, the intruder deferred to his consultant and picked one of the most elaborately decorated—the cup of a king rather than the cup of a servant. I’m reminded of that scene every time I hear about a Board of Directors making an exceptionally great or an unfortunately poor choice to lead their organization. Video clip from the movie.

“You have chosen…poorly,” said the knight guarding the Holy Grail. The famous line from the movie “Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark,” was spoken as an intruder tried to select the of cup of Christ from over a dozen options. If he chose well, he would live forever. However, the intruder deferred to his consultant and picked one of the most elaborately decorated—the cup of a king rather than the cup of a servant. I’m reminded of that scene every time I hear about a Board of Directors making an exceptionally great or an unfortunately poor choice to lead their organization. Video clip from the movie.

THE BOARD ON THE CLOCK

At nonprofit organizations, employee turnover among the development staff is an ongoing human resources issue. As you have probably heard, the average tenure of a development professional is less than 18 months. Over time, this “search-and-replace” function is formalized at larger institutions, and an experienced Director of Human Resources can handle almost anything related to employee resignations, retirements, or dismissals. This process is tweaked and revised year after year under the direct or indirect supervision of the organization’s chief executive.

Then one day that chief executive resigns, retires, or is dismissed. Ready or not, the Board of Directors suddenly becomes responsible for conducting the search that will replace the one employee who reports to them. That responsibility is highly critical to the organization’s future and can be very costly to the organization’s donors. It is potentially devastating to both if not done well.

That being said, turnover at the top is a pivotal moment in the history of an organization, giving the board of directors an opportunity to press the reset button with regard to leadership style, skill-set, and strategy. Regardless of the real reason for the departure and whether board members consider it a catastrophe or an answer to prayer, the fact remains—the Board of Directors who have served in the background as supervisors and advisors to the CEO are now operationally on the clock with a most important task at hand.

A SERIES OF UNFORTUNATE EVENTS

I had a long conversation with a board member recently that closely mirrors the scenario I’ve just described. For over three decades, their university had benefited from the extraordinary leadership of a truly great president who was highly respected by everyone throughout the institution—including the donors. Consequently, he was instrumental in securing many large gifts for the university. He got them through the 1980’s at a time when some were predicting that half the private colleges would go under. He led the university through the near economic collapse of 2007 and the recession that followed. The long-time president had notified the board of directors about his intention to retire on more than one occasion but was repeatedly encouraged to stay through another semester or for another campaign. Finally, he told the board that he was done. It is hard to believe that the Board of Directors had not developed a well thought-out succession plan. A survey of corporate executives by Deloitte, a human resources research and consulting group, revealed that only 14% of companies describe themselves as being “strong on succession planning throughout the organization.”

What followed the esteemed president’s departure is a scenario I’ve seen too many times. After several succession options do not work out and in the continued absence of a CEO, busy board members are increasingly being called upon to get involved. They feel the need to meet with major donors and staff to assure them that everything is under control. Amid the mounting pressure to quickly make a selection, sometimes they strike gold. Sometimes (like this time) they choose poorly. In stark contrast to the demeanor and leadership style of his predecessor, the newly selected president came off aloof and arrogant. That doesn’t necessarily mean the new president was an aloof and arrogant person. You have to separate the person from the performance. Perhaps it was his presumption about effective leadership styles, or he just found himself in way over his head. Regardless of his personal intentions, his performance was causing many problems, primarily the departure of staff at many levels of the institution.

TRUE LOSS AND COST

We have all heard about the high cost of turnover among key staff—presidents, vice-presidents, and directors of this and that. I include fundraisers among those key leaders because they are the so-called “rainmakers” for an organization. True costs of executive turnover are usually underestimated, even among board members who have gone through several CEO transitions. The reason for the underestimations is that, in addition to the basic costs of a new leader search, it’s the intangible costs that really take a toll on an organization. Three primary loses:

The loss of intellectual capital (systems): It takes years to create, manage, and train staff in an effective system of fundraising. However, that well-oiled machine will grind to a halt if a new leader doesn’t have the knowledge or experience to run it.

The loss of social capital (relationships): I frequently hear stories about organizations in some degree of crisis because donors no longer know anyone at the organization. If you are the third fundraiser in five years assigned to them (i.e. the average tenure of fundraisers), those donors may be less interested in meeting or talking with you.

The loss of momentum: It’s hard to quantify the benefits of positive momentum, but fundraisers are well acquainted with the power of it. Making a solicitation for funding always requires a step of faith, and once you stop for a time, it’s hard to regain that momentum.

For these reasons and more, it’s often the mid- to lower-level fundraisers who are most aware of the true loss and cost of leadership turnover.

BENEFIT OF THE RIGHT LEADER

Last month I spoke at a meeting of the board of directors at a healthcare system that is one of the best examples of employee retention and succession planning I have ever seen. I hope to tell that story in the coming months. For now, I just want to highlight a few of the benefits of finding the right person to lead the organization into the future.

It’s often the mid- to lower-level fundraisers who are most aware of the true loss and cost of leadership turnover.

1. Trust—The greatest CEOs and CDOs (chief development officers) I’ve known are truly donor-centered. They’re in it for the long haul, and it’s not worth taking shortcuts for expediency. No single gift is worth leaving a donor feeling pressured, unappreciated, or manipulated.

2. Respect—His or her personal profile and reputation are above transactional relationships. Respect is a two-way street. It is not just about closing the deal but building and developing donor relationships.

3. Attraction—CEOs, CDOs, and planned giving officers at the most advanced levels attract donors. In other words, in addition to their funding proposals and solicitations, donors seek them out for giving and estate planning advice. This is rarified air for nonprofit executives, but it is a characteristic of the great leaders who have established their professional profile among organizational donors.

4. Confidence—In difficult times, donors look to these individuals for assurance that the organization is going to be okay. And it’s not always the chief executive. Sometime it is the Vice President or even a longtime fundraiser donors look to for assurance.

5. Associative Properties— Irrespective of other ills and woes, donors and volunteers tend to transfer by association the qualities of a great leader to other leaders and to the organization as a whole.

6, Inspiration and Vision—A characteristic that’s low on the list of many leadership searches; however, in terms of staff turnover and donor retention, nothing could be more important for an organization.

THE CAUTIONARY TALE

The university president in my story above excelled in each of these six leadership characteristics. However, they wound up choosing a new leader who was deficient in almost all of them. I’m not sure of all the reasons it turned out that way. Perhaps they did not understand what it was that had made the previous president so successful; or possibly they were looking for a leader with new ideas, a new leadership style, or new ways of doing things. In that case, they seem to hire they the leader they were searching for.

The university president in my story above excelled in each of these six leadership characteristics. However, they wound up choosing a new leader who was deficient in almost all of them.

Nonprofit boards in the face of mounting pressured need to resist the temptation to make a quick hiring decision. Jim Collins, the author of Good to Great, Great by Choice, and several other books on the characteristics of great companies, commented, “The old adage, ‘People are your most important asset,’ is wrong. People are not your most important asset. The right people are.” Choosing the organization’s next leader is a rare opportunity and responsibility. No other decision will have more impact on the viability and effectiveness of your organization.

Eddie Thompson, Ed.D., FCEP

Founder and CEO, Thompson & Associates

Copyright 2018, R. Edward Thompson

Excellent article Eddie! So sad that organizations often have the talent in house who only need the chance to show their leadership. True leadership development and succession planning could reduce the short tenures (since that is usually the only way to climb the ladder) and serve the organization exceptionally well.

I have been involved with development/fundraising for more than 40 years and relationships with prospects and donors are number one on the priority list for success. The turnover battle is directly against this success. It takes years to develop strong relationships and we turn development officers every 18 months. The math does not add up. And…the higher up the giving pyramid, the more important the relationship.